SEARCHING FOR HIS OWN SELF

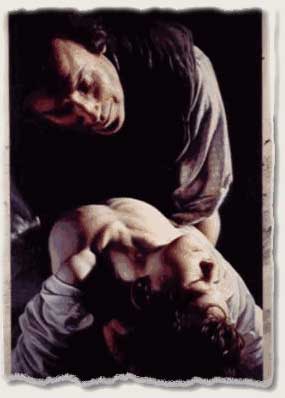

Star tenor Neil Shicoff is back in Vienna, rehearsing Verdi´s Ernani at the state opera in November. He can also be admired in two of his most famous roles: as sensitive poet Lenski in Eugen Onegin and as rough sailor Peter Grimes.

Tenors have traditionally been hailed as the true gods of opera, not only since the "holy trinity" consisting of José Carreras, Placido Domingo and Luciano Pavarotti has been revered on the altar of that particular art form. By the late 18th century, tenors were already beginning to overtake the castrati, whose voices had up to then had an almost magical erotic fascination. But only after the rise of the middle classes, who in their battle against the "decadent" nobility had pledged themselves to "naturalness" in all walks of life, was the heyday of the castrati well and truly over. Mozart was the first famous composer to give the roles of emphatic young men in his operas to tenors. In the early 19th century, the works of Bellini and Donizetti finally created the stereotypical image for tenors that is still valid today: the tenor as a romantic hero and sensitive lover.

Tenors have traditionally been hailed as the true gods of opera, not only since the "holy trinity" consisting of José Carreras, Placido Domingo and Luciano Pavarotti has been revered on the altar of that particular art form. By the late 18th century, tenors were already beginning to overtake the castrati, whose voices had up to then had an almost magical erotic fascination. But only after the rise of the middle classes, who in their battle against the "decadent" nobility had pledged themselves to "naturalness" in all walks of life, was the heyday of the castrati well and truly over. Mozart was the first famous composer to give the roles of emphatic young men in his operas to tenors. In the early 19th century, the works of Bellini and Donizetti finally created the stereotypical image for tenors that is still valid today: the tenor as a romantic hero and sensitive lover.What makes a good tenor is a brilliant timbre and crystal-clear high notes. This has contributed to the fact that tenors are seen as dazzling heroes even if the plot of an opera dooms them to failure or ruin. Only recently has this glorious image been slightly modified: There now is a singer who does not see himself primarily as a supplier of top Cs, even though he is perfectly capable of delivering them anytime, but who dares to explore the psychological depths of each role and is more fascinated by failures than by glorious heroes: Neil Shicoff.

THE ANTI-HERO

Shicoff has a weakness for broken characters, those who have lost their balance and are struggling in vain to restore it. "I can understand such characters very well", the 49-year old singer admits. Shicoff was born in New York as the son of a cantor of Russian descent and studied singing with Jenny Tourel at the Juillard School. "My character has a lot of dark sides and deep chasms. When I am alone, when I can´t sleep at night and sit down at my computer instead or wander through the streets in the early hours of the morning, I feel that characters such as Hoffmann or Peter Grimes are part of my own personality." His destructive traits would probably make him an outlaw if he gave in to them completely. "I think I´d turn into an alcoholic", Neil Shicoff confesses. "But the stage protects me from that. For me, the stage is like a valve where I can give vent to everything that might be dangerous for me in real life and where I learn a great deal about myself."

Neil Shicoff compares himself to a boat which is tossed to and fro on the high seas. For a long time, he was unable to find a safe harbour where he would be protected from the storms and could finally drop anchor. His sensitivity, a prerequisite for his stunning performances as a singer, made it difficult for him to adapt to opera life, which demands smooth adjustment and prompt performance from all its members. Engaging Neil Shicoff therefore constituted a risk for all opera houses. When he didn´t feel up to a performance, he would simply cancel it – due to this, his career seemed seriously in danger only a few years ago, and it was anything but certain if he would be able to make it to the very top.

THE TRANSFORMATION

But Neil Shicoff has most definitely made it. He is back, and has managed to always stay true to himself. After a soul-destroying divorce, he has finally found his safe harbour with his second wife, the singer Dawn Kotoski, who gives him the stability and support that he needs. His marriage has transformed him. "I used to be an arrogant egocentric, and think that what I was doing in the theatre was the most important thing on earth. I don´t believe that anymore. The most important thing in my life now is my family, my daughter, my second wife and my son Alexander. They are more important than my need to express myself. If I had to make a choice, I would not hesitate to give up my career for them."

Seeing his son Alexander grow up means a lot to Shicoff. "I admire his personality. It is larger than my own, and he is also totally different from me in his way of dealing with people. I am very reserved and withdrawn, and can only be myself with my family, with very close friends or on stage. Alexander, on the other hand, is very open with people, frank and incredibly creative." In order to see his son growing up, Neil Shicoff is prepared to go to great lengths, such as last October: "Alexander goes to school in Zurich, and I was singing Don Carlo in Paris. Almost after every performance, I took the plane to Zurich to wake Alexander at half past seven in the morning, prepare his lunchbox and take him to school. Things like that give stability to my life."

But Neil Shicoff still freely admits that there are darker sides to his personality, but that he has learned to deal with them in a better way. When after a performance he feels that he has not penetrated far enough into the depths of a character, he is still disappointed, but has learned to cope. "Such things used to completely throw me. Today I see them as an incentive to do better next time." But most importantly, Shicoff has learned to see himself as part of a bigger whole. "As a singer, I am more willing to compromise than I used to be, but that doesn´t mean that I sacrifice my ideals. It means that I am open to other people, such as the director or my partner on stage. Each of us brings a certain colour into a production, and we have to try to harmonise these different colours. I used to be totally different and always try to get my own way in everything."

LONGING FOR SECURITY

One factor is still extremely important to Shicoff: The environment where he works. He has to feel accepted to give his best. "That was the case with the Don Carlo production in Paris. I worked almost exclusively with friends, such as Caroll Vaness, Samuel Ramey and Vladimir Chernov. James Conlon, who has witnessed my career from the very start, was the conductor and Graham Vick, who I greatly admire, was the director. When I am lucky enough to work in such an atmosphere, it can really change my way of looking at the part."

Neil Shicoff expects similar impulses from his next premiere at the Vienna State Opera, again with Graham Vick as the director. The opera performed will be Ernani, one of Verdi´s early works, and the premiere will take place on December 14th. So far, Neil Shicoff has had mixed feelings about the rebellious hero, one of the star roles of his great idol, Franco Corelli. "I sang Ernani in 1975 with James Levine as the conductor, when I stood in for Richard Tucker – that was very early in my career. About 20 years later, in Bilbao, I wasn´t in optimum form, and only last year in Zurich did I feel that my view of Ernani has somehow changed to the better. However, I still haven´t got to the very core of his character. I hope that this will happen in Vienna, though."

ARTISTIC HOME VIENNA

Vienna is a very special place for Neil Shicoff. He has sung almost all of his great roles at the Vienna State Opera, and even wrote interpreting history as Peter Grimes in Benjamin Britten´s opera. "My relationship to the Viennese audience is unique. When I come on stage, I can actually feel that people like me, and because of that, I am able to give 150 percent. When people are less enthusiastic, I simply cannot give my soul." In his hymn on Vienna, the star tenor also includes the head of the State Opera: "Mr. Holender creates an atmosphere in the house where I feel protected and secure. Whenever I have a problem, I know I can count on him. I have a similar feeling with Alexander Pereira in Zurich. I think that even if I rang him at three o´clock in the morning, he wouldn´t be angry but would simply ask where he should meet me."

DEBUT IN SALZBURG

The Vienna State Opera, the Opera House in Zurich and the Metropolitan Opera in New York constitute that magic triangle on the lines of which Shicoff´s international career is moving. Other stops are the Opéra Bastille in Paris, the Bavarian State Opera in Munich and in the future, possibly the Salzburg Festival, where he gave his, albeit short but overdue, debut last summer, standing in as Don Carlo. "I am proud of having sung in Salzburg. There are negotiations underway about another performance there, and I am sure that we are going to reach a satisfying conclusion eventually." However, it is improbable that Shicoff will sing a Mozart part in Salzburg, although his name was mentioned for a new Idomeneo in Zurich, with Nikolaus Harnoncourt as the conductor. "We did have preliminary talks, but unfortunately they didn´t come to anything." Still, Shicoff is the proud owner of a precious Mozart autograph: "It is a letter written by Mozart in 1788, in which he asks Michael Puchberg for money. I love this letter, I find it very touching. I will probably loan it to the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra."

Shicoff´s record career has also taken off again, after coming to a near-standstill for a short while. A Puccini-album came out recently, on which he sings scenes from Manon Lescaut and Tosca together with Galina Gorchakova. For February, two more opera recordings are planned: Aroldo by Verdi, conducted by Fabio Luisi, and Il Tabarro by Puccini, conducted by Antonio Pappano. "So far, I have only been truly happy with one of my recordings, Eugen Onegin conducted by Semyon Bychkov.", he confesses. "But I think that both Aroldo and Il Tabarro are very good recordings, and I hope that other such projects will ensue in the future. I have to confess that I have changed a lot in this respect, too, and that I´d like to make more recordings."

DANGEROUS IDOLS

Neil Shicoff does not agree with the idea that he, like many others of his generations, had a hard time trying to step out of the shadow of the Three Tenors and to make a name for himself faced with such competitors. "No, the fact that the record bosses dumped me was the price I had to pay for being so difficult and incapable of adapting to the conditions of bringing off a production. It had nothing whatsoever to do with the Three Tenors. The danger for my generation lies elsewhere, I think – we are tempted to model ourselves on Placido Domingo. His talent is immense, his physical capacity unique and he is incredibly intelligent into the bargain. These factors together make him a very special personality in the world of opera, because they enabled him to develop his repertory in a way that is simply impossible for anyone else. A tenor who orientates himself on Domingo and tries to copy him in this respect is in danger of burning himself out."

Neil Shicoff has easily evaded this danger and, in the meantime, has himself become a dangerous role model for younger tenors. Neil Shicoff, too, is unique and can neither be copied nor imitated. This he proves again and again, every time he appears on stage.